For humans, communication is all about sight and sound, but, for many other organisms, chemicals are their primary language. We occasionally see this type of communication in action — the dog sniffing a rock and leaving his return message with a raised leg — but most of the chemical conversations going on around us are hidden from our perceptions.

We’ve identified some of these communications, and it’s pretty wondrous. Young queen honey bees, out for their nuptial flights, trail an it’s-time-to-mate scent. Pathogenic bacteria lie quietly inside a host and send out “I’m here” signals, releasing their toxins only when enough are present to potentially overcome the host’s immune system. A tree under attack may release chemicals that nearby relatives recognize as signs of impending disaster, allowing them to prepare their own defensive weaponry. Despite discoveries like these, we still understand little of the chemical conversations floating around us.

A study published in November in the Annals of the Entomological Society of America opens a window onto this means of communication for one sophisticated insect predator, Vespa soror, a giant hornet that is kin to the one that sparked a media frenzy in 2020.

Vespa soror, like its infamous cousin, is a highly social insect whose workers occasionally coordinate to attack a honey bee colony en masse. These attacks happen in the fall when hornet colonies have grown large and have many mouths to feed. Heather Mattila, Ph.D., a professor at Wellesley College, is lead author of the Annals paper. (Her work finding that Apis cerana honey bees emit alarm sounds to warn colony members of hornet attacks has also recently earned public attention.) She says that, in typical giant hornet behavior, individuals grab whatever food they can get on their own. Come fall, however, they sometimes switch to group predation, “this full court press effort to try and take over a whole colony.” How do V. soror hornets choose a honey bee colony for mass attack? And how do they let their relatives know?

Scientists know that social insects communicate with each other (and sometimes other species as well) via chemicals released from exocrine glands — glands that secrete something outside the animal’s body. In this study, Mattila and colleagues investigate two of those glands: the van der Vecht and Richards’ glands. These glands are found only in certain eusocial wasps in the Vespinae and Polistinae subfamilies. No other wasps, bees, or ants have these glands. The researchers looked in detail at the structure of the glands, a first step in better understanding their purpose. They also studied the hornets’ rubbing behavior at a honey bee apiary to try and assess which glands are involved and the rubbings’ role in mass attacks. (See videos at https://videos.files.wordpress.com/zqPgIkgZ/vespa-soror-rubbing-bee-hive-1.mp4.)

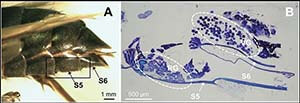

Both glands are located toward the end of the gaster — the part of a hymenopteran that is behind the “waist.” The Richards’ gland is smooth while the van der Vecht gland has a large brush of hair. Each gland is tucked under a sternite — one of the little plates on the underside of an insect. In certain body positions a gland is exposed, and in others the sternite acts as a kind of cap. “They have this structure that allows them to produce the pheromone but then release it to the world when they change their body posture, and part of that change in body posture could very well be rubbing,” Mattila says.

Because the glands are on the underside of the insect, it’s difficult to see which are involved in the rubbing. Nevertheless, the authors write, “Observations confirm that the van der Vecht gland is exposed during gastral rubbing but that the Richards’ gland and glands associated with the sting apparatus may also contribute to a marking pheromone.”

The scientists recorded V. soror activity over several days at an Apis cerana apiary in Vietnam. Lots of hornets were present during the study period. “Just hornets at a salad bar,” Mattila says, “grazing and grabbing bees,” and sometimes rubbing their hind ends on nest boxes or overhead vegetation. Some colonies weren’t marked or received only a rub or two. “We saw lots of marking going on that didn’t lead to a massive attack,” Mattila says. Some colonies, however, were heavily rubbed — and that heavy marking mattered. At one colony that received 26 rubbings over three hours, the hornets had, the authors write, “transitioned from hunting to attempting to breach the nest entrance.” Mattila says, “we feel pretty confident these things are linked.”

Mattila notes that a lot more work needs to be done to understand how giant hornets communicate. “I kind of cringe sometimes thinking about this whole ‘murder hornet’ label, because these are really incredible animals. They are really beautiful creatures that are doing something hardly any other social insect does,” Mattila says. “And it’s fun to see up close how their parts are built for this.”