After the spring nectar flow and swarming have passed, the weather conditions become hotter and drier as summer arrives. During this time, I watch for usurpation swarms. A usurpation swarm is typically a small summer swarm that invades even a numerically strong queen-right colony. The mother queen of the colony is eliminated and replaced by the usurpation queen from the swarm. This bee behavior is relatively new to North American beekeeping.

Understand the ramifications of what occurrs with this takeover. What appears like a small absconding swarm, destined to die, never to survive the winter, by the out-dated “old rules” of bee biology, can now survive ― in “grand style” I might add. By taking over a large colony, the small usurpation swarm acquires its vast honey stores and combs. It does not matter if numerous bees of the usurpation swarm are killed, fighting with bees of the large (host) colony. As long as the usurpation queen survives (and the mother queen dies), the genotype (genetics) of the colony changes to become the usurpation colony.

From my study of honey bees, the way I think about my bees has changed too. I have come to regard the summer as “usurpation season.” Usurpation activity varies in different summers, and apparently not all summer swarms are usurpation swarms (a complication). Moreover, usurpation bees do not differ in body color or temperament from the gentle feral bees I trap in my bait hives from the woods in Piedmont Virginia. Although I can be quite suspicious of a swarm as being a usurpation swarm, the only sure way I know a swarm is indeed a usurpation swarm is when I observe the bees usurp a colony, or I see recent evidence of a takeover (see below).

What follows are some of my experiences from the past 10 years of observing and photographing usurpation swarms. These situations should be similar to what a beekeeper would encounter. (The context will begin with a small summer swarm, suspected of being a usurpation swarm.)

Upon finding a small summer swarm that has landed near an apiary, it is easy to assume the swarm came from those hives. However not always, when considering usurpation behavior. The swarm could have come to the apiary from an unknown bee source. Swarms arriving at an apiary are not the typical way we think about them, but with usurpation some old ways of thinking need to change.

When I find these swarms around my hives, the bees are usually not engorged with honey, certainly nothing like the numerous bees with distended abdomens comprising a spring reproductive swarm (where the swarm fissions from its parent colony producing another colony). These summer swarms may be on the wing for several days, consuming the food they carry. So how do they survive? The bees do something I have never observed from spring swarms.

The bees from a summer swarm forage for nectar (at least some of them) (see Figure 1). Beginning during the cool summer morning and continuing later in the day, some bees on the cluster avidly unloaded returning nectar foragers. Sometimes three receiving bees unloaded one forager. (During food transfer the receiving bee extends the tip of her tongue into the open mandibles of the donor bee, who holds a drop of nectar between them. So three receiving bees had their tongues between the mandibles of one forager bee.) Concurrently, bees waggle danced on the cluster of the swarm. I doubt these dances indicated nest sites, as would be expected with spring reproductive swarms. Most likely, these dances indicated profitable nectar resources, since host colonies were nearby. (The dances did not appear to be migratory dances either.)

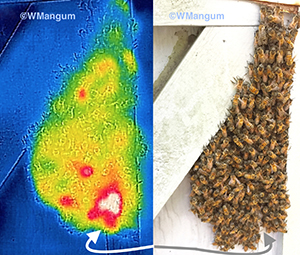

Any summer swarm that has landed on a hive, particularly directly under the entrance/alighting board, is a cause of heightened concern that usurpation is occurring or soon to occur. (I am assuming here a solid wooden bottom board.) With the swarm under an entrance, I have seen the usurpation occur or sometimes the swarm just departs. The conditions distinguishing the two outcomes are unclear.

A beekeeper once reported a swarm under the hive with a screen bottom board that opened to the ground. From the report, it appeared that most of the bees did not enter the hive. With the swarm bees in contact with the hive bees through the screen, that might have confused the usurpation process. The swarm was also displaced too far back under the hive, in the shadows, which may have disrupted the bees from moving into the hive. (My advice here would be to look for a queen(s) being balled in the cluster or on the ground below the swarm cluster. Once you have the queens you have control over the swarm. See below for more details.)

While a swarm can be clustered under a hive entrance for days, some colony invasions happen quickly, in less than half an hour. It is easy for a beekeeper to miss that ….