Imagine you’re playing a word association game such as Password and your secret word is “bee.” The clues you might give to elicit that word include “honey,” “sting,” and “swarm.” But “legs”? Never. Nothing about legs reminds us of bees.

Yet bees, especially honey bees, have some of the niftiest legs in the animal kingdom. Although they don’t hold a candle to millipedes for quantity or harvestmen for length, they beat them hands-down for function. Honey bee legs are like mini Swiss army knives: creatively designed and compactly stored tools for every purpose.

The thorax is an insect’s transportation hub

Like all insects, honey bees have six legs, each arising from the thorax alongside the wings. But in honey bees, each leg pair has a unique structure, making each pair noticeably different from the others. And each pair performs unique functions for the multitasking honey bee.

Although the bee uses all three pairs for walking and dancing, they also perform rare feats we seldom associate with legs. For example, a honey bee’s legs including the attached feet (tarsal claws) can taste and smell — truly amazing stunts for legs and feet(s).

Features all six legs have in common

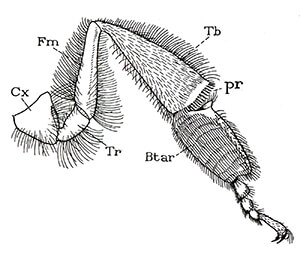

Before we look at leg differences, let’s look at their similarities. First, all bee legs have five segments. Beginning at the thorax and working out, we have the coxa, trochanter, femur, tibia, and tarsus. Some of these parts may be unfamiliar to you, but some you know, which makes them easy to learn.

For example, you have a femur in your upper leg and a tibia in your lower leg. These come together in a joint called the knee. In addition, you have a protective plate covering the joint called a kneecap or patella.

In comparison, a bee has six knees in exactly the same place — between each femur and tibia. Although most bee species also have a protective shield (a kneecap of sorts) at the basal end of the rear tibia, these are conspicuously absent in honey bees. Ground-dwelling bees use these basitibial plates to brace themselves in the dirt while digging so they don’t lose traction or slip and tumble into the hole.

At the far end of your human tibia, you have a foot that is made of many smaller bones that aid in balance and movement. Similarly, the bee foot (or tarsus) comprises five subsegments that help the bee with balance and movement.

The five subsegments of the tarsus are called tarsomeres. The first tarsomere, closest to the bee’s body, is called the basitarsus and the last one is called the pretarsus or distitarsus (the toe).1 In honey bees, the far (distal) end of the pretarsus sports two claws (called tarsal claws).

Five leg segments or six?

In older publications, it is common to find mention of six leg segments instead of five. The discrepancy involves the tarsus, and the question is whether the pretarsus should be regarded as a separate leg segment or included in the tarsus as a fifth subsegment. Since the current literature usually names five subsegments within the tarsus, I’m using that convention. Just remember that you may see it reported differently.

Between the tarsal claws, you can find the arolium, which is an adhesive pad covered with tiny hairs. The pads are useful for walking on vertical or inverted surfaces and enabling the bees to navigate irregular or slippery substrates. The arolium and the tarsal claws are extensions of the pretarsus.

Bee legs come in different lengths

Even though all six legs of the honey bee have the same segments, each pair of legs is a different length. And it’s not surprising to learn that worker legs differ from queen legs which differ from drone legs. Because each type of bee has a unique role to play within the colony, its legs evolved to fit the job.

In worker bees, the forelegs are the shortest, followed by the mid-legs, and the longest by far are the hind legs. The queen’s legs follow the same pattern, but overall her legs are longer because she has a bigger body. In addition, the queen carries her legs splayed out to the side like a water strider, which makes them appear even longer.

Around the hive, both workers and drones keep their legs tucked under their bodies. Bees flying long distances tuck them out of the way too, although workers dangle their legs before landing, looking much like an airplane’s landing gear.

All insect legs follow a similar model but they each have adaptations that help them with life in their unique environment. Various types of bees have quirky takes on the same parts, many of which can help taxonomists determine a bee’s genus.

A leg for every purpose

With some glaring exceptions, honey bees use their legs like we use our hands and feet. Here are some everyday uses for three pairs of honey bee legs.

- Walking, running, landing, and dancing: Honey bees can opt for a leisurely stroll along the landing board, a vertical wall walk, or a frolic across the ceiling just because it’s there. When alighting with a load of cargo, the legs feature all the shock absorbers and sticky pads necessary for safe and gentle arrival. And best of all, when a bee feels like dancing, all those legs mesh like a finely tooled machine. Allemande left and promenade right — it’s so easy when you know the steps.

- Grasping: Times are many when a bee just wants to latch on and hold tight. When the wind is tossing her flower erratically, when she and her sisters decide to build a scaffold for comb construction, or when drone dispatching appears on the agenda, those tarsal claws come in mighty handy.

- Grooming and scratching: Bees comb their bristly articulated legs across their bodies to gather pollen and remove accumulated dirt and grime. And now and then, bees appear to take a scratch just like everyone else. Some researchers believe the European honey bee is adept at grooming away tracheal mites, something we’ve paid little attention to in recent years.2

- Tasting and smelling: Honey bees have multiple receptors for taste and smell. We find some on the mouthparts and antennae, but surprisingly, some are on the tarsi. Hair-like sensory organs called sensilla can detect both the taste and odor of things the bee walks on. The bees send their findings to the brain, which “decides” if the substance is a suitable food source.

- Pollen collecting: Honey bee legs have a major role in pollen acquisition. Most leg segments of the honey bee are covered with some type of hair that facilitates pollen collection, although the density, length, and thickness of hairs vary depending on their location and exact purpose.

Some legs are better equipped than others for certain jobs, so let’s look at each pair of legs and its specialized equipment.

Features of the honey bee’s forelegs

Although the forelegs are the honey bee’s shortest pair, what they lack in length they make up in function. For example, it’s the foreleg tarsi that harbor the sensilla for taste and smell.

In addition, each foreleg has an antenna cleaner built right in. The antenna cleaner comprises two parts: a round notch in the basitarsus, which is outfitted with stiff hairs, and a corresponding spur on the tibia.

To make it work, a bee simply lifts her foreleg over her own antenna, and then flexes her leg. This movement makes the ….