We finish up this queen introduction series with a method that I recommend. I realize beekeepers have numerous ways to introduce queens. In historical beekeeping, even more queen introduction methods abound. In 1948, L.E. Snelgrove published “The Introduction of Queen Bees,” a book on the subject. Consider now a practical, familiar, and reliable method, drawing on the results of the previous articles.

For me queen introduction actually starts by having the queens arrive in good condition, spending as little time as possible in transit. I have them shipped overnight by one of the large commercial carriers. Getting queens so quickly is expensive, but for me it’s worth it, given the cost of queens.

When the queens arrive, I unpack them and inspect the bees, making sure the queens are alive and undamaged. Pay particular attention to the queen’s feet, where hostile bees may have bitten them. A damaged foot may display a skipping-leg motion over the brood comb (held vertically), because missing hooks on the foot cannot grasp the cell rims. Such a queen could be subject to early supersedure.

While being held before installation in the hive, the caged bees need water. I give them water by smearing it over a few meshes of the cage (see Figure 1). I watch the bees as they drink the water. If they take it all, I give them a bit more. Continue in the same manner until they stop taking it. In this way the bees are telling me when they have enough water. Sometimes new beekeepers put too much water on the screen all at once; little by little is better and safer for the bees. At least once a day I check to see if the bees need water, here in Virginia. In less humid regions, more water checks may be needed. Keep the queens at room temperature in a dark room with no drafts.

Before installing the queen cage in the hive, of course, the colony must be queenless. My procedure is to first find the old queen and remove her, then prepare the queen cage and install it without any delay. For queen finding, I work through the brood nest with a minimum of smoke and vibration. Usually I can find four to five queens per hour, unless I am tired or I am having a “bad queen-finding day.” It helps me greatly to find the first couple of queens quickly to set my pace. If I go through a hive and cannot find the queen, I check it again quickly. If I still do not see her, and there is a typical brood nest with eggs, indicating a queen is present, then I close that hive. Do not waste a lot of time and energy trying to find a queen who might be hiding. Just go to the next hive and look for that queen (or do some other apiary work if you are only requeening one colony). Later on look for that queen again. This time the frames will be easier to remove because the propolis and burr combs were just broken from the first inspection, resulting in a lot less vibration.

When searching for queens, resist the temptation to scrape burr comb off top bars or remove excess propolis. That just creates more vibration, disturbs the bees, and slows finding the queen. Since you have new queens waiting to be introduced, finding the old queens takes priority over other jobs that can be done with a more flexible schedule. Of course for hives with queens remaining unfound, scrape burr comb upon leaving the colony to make the next search easier.

We know bees will not accept another queen when they have one — even if they have a virgin queen or defective queen, and you are introducing a functional laying queen. We saw in the previous article where one colony had two queens (Hive 60NA), and removing one queen did not make the colony queenless. The queen introduction should have failed. Except that with the candy release blocked, Hive 60NA showed prolonged balling, indicating the presence of a second queen.

The two queens situation can arise during natural queen replacement when the mother and daughter coexist for a while in the colony. When using the candy release method, unless the new queen was marked or obviously a different color from the second queen, one may never know that she was, in fact, killed. Since beekeepers do not know which colonies might even have second queens, they would waste a lot of time searching for second queens that usually will not be there. The usual management practice is to assume that removing the (first found) queen dequeens the colony.

After dequeening the colony, I install the queen cage immediately, that is, without waiting a day or so as some beekeepers do. Mainly I don’t wait to save a second trip to the apiary. Concerning the delay, the thinking here is that it allows bees to sense her absence (which they will) and perhaps begin to forget her particular odor (which is more problematic). For the latter, it would be interesting to see if the delay would make a difference with the aggression patterns (balling) on the cages or queen acceptance.

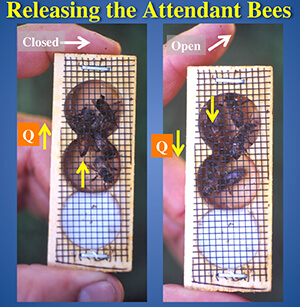

After removing the old queen, I prepare the queen cage for installation, dealing with the candy and the attendants. A cork usually covers the exit hole at the candy end of the cage. It must be removed because this is the exit for the queen. Now we come to a difference of opinion. Some beekeepers advise poking a small hole through the candy to make it easier for the bees to release the queen. Others recommend not making a hole in the candy. Instead of relying on some absolute rule, which may not always apply for a particular situation, I make my decision based on the consistency of the candy as I find it. Using a small nail, I make a dent in the candy. If it feels soft, then I do not make the hole. If it feels hard, or a little crusty and dry, then I make a small hole through about a third of the candy (not all the way through).

In this queen introduction series, we saw inside the exit hole of a queen cage, where a bee was removing candy. That candy removal occurs –– all the time. At first the bee’s abdomen sticks out of the cage hole. Then taking turns, the bees slowly disappear as they deepen the hole. When there’s enough room in the candy, two or more bees ….