This month we explore the little-known realm of queen cell cups, when worker bees lay eggs in them. How exotic is that?

Queen cell cups are small cup-like structures that form the base of queen cells built for swarming or queen supersedure (replacement). Figure 1 shows a queen cell cup.

Beekeeping slang can be confusing for new beekeepers so here it is for queen cell cups versus queen cells. When empty, a queen cell cup is called just that. When containing an egg, mostly I hear beekeepers still call the structure a queen cell cup (not a queen cell). The discussion occurs mostly with swarming, a situation when the bees may remove the eggs from the queen cell cups, which would delay swarming. When a larva is in the structure, then it is called a queen cell.

The number of queen cell cups varies from colony to colony. I have found a colony with as many as 40 queen cell cups while next to it another colony of similar size may have only five. In addition, colonies tend to have more queen cell cups when the brood nest is large, as in the spring. Later in the season, the bees dismantle many queen cell cups as the brood nest decreases. The bees seem to regulate the number of queen cell cups in the colony for the current conditions, though much of the mechanics is unknown.

Knowing queen cell cup regulation was important when I studied laying workers in a single-comb observation colony. The small colony maintained only about four queen cell cups. Figure 2 shows the observation hive in my bee house that holds 30 of these hives.

Beekeepers commonly know that laying workers will lay multiple eggs in brood cells, the signature of a hopelessly queenless colony. Less well known is the activity of laying workers at queen cell cups. Laying workers will lay multiple eggs in them too, and I wanted to photograph that behavior.

So if I just transplanted, for example, ten queen cell cups into a small colony, that would give plenty of opportunities to see laying workers in them. That approach would be good for me, but what about the bees? They are already regulating the number of queen cell cups to be about four. Then suddenly and abruptly the bees would perceive they have too many queen cell cups. Intuitively, I would expect them to destroy quickly most, or even all, of the foreign queen cell cups.

In addition to too many transplanted queen cell cups, other potentially complicating factors could influence their acceptance. For example, these transplanted queen cell cups would come from queen-right colonies. They would have queen pheromones on them, which might affect the bees’ reaction in the observation hive. Also the exact place I attach the queen cell cups on the comb, even their distance from each other, may affect whether the bees destroy them.

In order not to disturb the number of queen cell cups too much, I just transplanted one or two at a time into the observation colony. I had be very careful not to dent the delicate sidewalls or distort the hole, keeping it perfectly circular. Cutting queen cell cups from combs of the donor colonies and attaching them to the observation hive comb, without damage, is more difficult than moving queen cells.

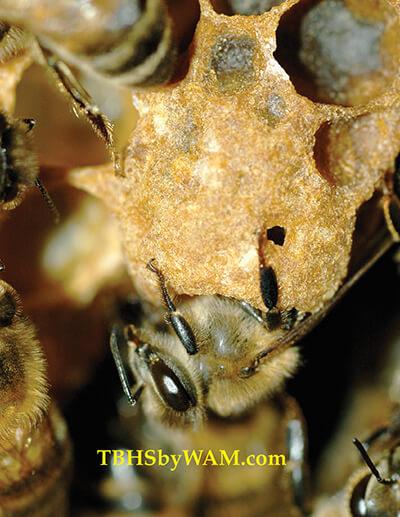

Immediately, numerous bees meticulously scrutinized the “new” queen cell cups. As expected, the bees destroyed some queen cell cups. On other attempts however, the bees accepted the queen cell cups, and worker bees laid in them within just two hours (see Figure 3).

I had observed and photographed worker bees laying eggs when they backed into a cell similar to a queen, which is called oviposition (see Figure 4), a sight beekeepers rarely see. In that situation, numerous cells across the comb provide oviposition sites. To photograph a laying worker in only one to four queen cell cups made for a more difficult and exotic event to photograph. After much tedious work with the bees, I produced Figure 5.

I felt there was more to see. I wanted to see the bees inside of the queen cell cup. Instead of transplanting an undamaged queen cell cup, I carefully sliced off about a quarter of it lengthwise. This bit of surgery revealed the cavity in the queen cell cup as seen from the side. To make a straight slice through the queen cell cup’s delicate sidewalls was not easy, even with a razor blade. Working under the dissecting microscope like a miniature auto-body mechanic, I repaired distortions in the sidewalls by gently pushing on the wax with a small probe until it regained the original shape.

Now for another twist. Instead of transplanting the queen cell cup to the brood comb, I attached the sliced queen cell cup to the glass so we could see inside it while it was in the brood nest. And at this juncture, a few important though subtle points need to be addressed about bees to enhance the chances of seeing a laying worker in the queen cell cup against the glass.

Some places on the brood comb had more laying worker activity than others. I marked the glass accordingly, so the queen cell cup would be near one of those active places. Next, to attach the queen cell cup, first I ….