For several months I’ve been talking about the honey bee colony as a superorganism: a group of individuals living together and resembling what humans would call a “society,” but which for various reasons is better understood as a special case of organism. For one thing, the group as a whole, not the individuals that make it up, constitutes a proper Darwinian unit of selection. And for another, the group as a collective does the kinds of things that only organisms do – is born, acquires resources from the environment, grows, reproduces, senesces, and dies. Another one of those organism kinds of things is thinking. But since none of us can get inside the thoughts of an animal, superorganism or otherwise, rather than call it “thinking” perhaps we should call it “group decision making,” because decision making is something we can observe and measure in the style of science.

When I speak to beekeeper groups I often use an analogy that helps explain what group decision making is, and is not. It goes like this: Before we arrived here this morning someone, maybe some of you, set up these chairs we’re sitting in now. I wasn’t here, but I can make a good guess what it looked like. Someone, say Tom, grabbed a chair from the stack and put it here. Why here? Because Tom had to put it somewhere, and this felt right. Next came George, and he put his chair here next to Tom’s. Why here? Because Tom had put his chair there first. Next came Ellen, and she put her chair next to George’s – and so on until the whole room was filled with orderly rows, complete with aisles that conveniently fit the dimension of the human beings who would be using them. Why did the aisles fit? Because it was humans who had to move around them as they set up the chairs. One action leads to the other. Pre-existing properties: the walls constraining the room, task-oriented humans, raw material to work with (the chairs), the body size of the humans doing the work, dictated the outcome – orderly rows and aisles. And it was the actions of individual actors, each responding to his or her immediate cues that “decided” the length of rows, the width of aisles, and their exact locations.

What I’d guess was not happening was some busybody directing the whole project. I can’t imagine President Bob standing in front of the room, pointing: “Tom, put your chair here. OK, now George you put your chair here, now Ellen put yours here.”

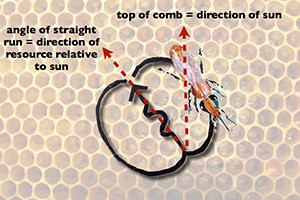

Group decision-making in the superorganism looks a lot like the former, but includes elements of the latter as well. Studying group thinking involves parsing out the effects of individuals – how each forages, how each appraises a resource, how each reacts; as well as to identify how the actions of individuals influence other individuals; as well as to identify the tipping points that commit the whole group to decide in favor of A instead of B. This level of thinking is perfectly adequate for the kinds of decisions faced by a honey bee superorganism – choosing nest sites, choosing foraging sites, optimizing the shape and configuration of its comb nest inside a hollow tree. The distinctives of group thinking are (1) independent actors, (2) each free to react appropriately to her local information, (3) each interchangeable to some degree, and (4) each freely contributing her information to the group, regardless of its quality. In addition, all actors are (5) free to respond to other actors, and (6) there is enough “biomass” (actors) to average out errors and arrive at an optimum decision for the group. This lateral heterarchical kind of thinking is in contrast to the top-down hierarchical kind of thinking in metazoan animals like ourselves …