Honey extractors evolved in America as the fledgling apiculture industry began to see the value of these machines. To understand that historical development from primary sources, I collect honey extractors, study them, and search how their original design functioned in the old bee literature.

I had to find one important design: an 1870s Novice Honey Extractor. A.I. Root made this extractor, beginning in the early days of the bee supply company he founded, the A.I. Root Company located in Medina, Ohio.

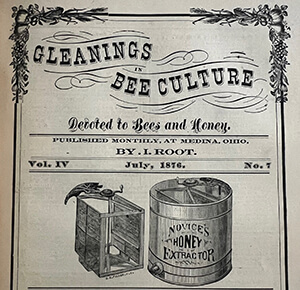

The extractor had “Novice” painted on it in large prominent letters. “Novice” was Root’s pen name used in his early bee writing. It was also in the original title of the bee journal begun by Root, known as “Novice’s Gleanings in Bee Culture” for its first year, 1873, before being shortened to “Gleanings in Bee Culture” (see Figure 1). Root’s magazine lives on, now known as “Bee Culture.”

In the 1870s, the growing A.I. Root Company mass-produced beekeeping equipment. Originally, I thought finding an early Novice extractor would be fairly easy. Reality was more complex. Early extractor versions were extremely difficult to find. Later versions were difficult to find in good condition from the outside. Beekeepers got more than their money’s worth from Root extractors.

Although Root extractors were built rugged tough, moving the extractors subjected them to dents and scrapes to the outside of the can. All that damage added up over the decades, along with time fading the paint. The artistic lettering and fancy borders turned to ghosts of their former beauty. Functionally undaunted though, the extractors could still spin out honey. A few other factors probably contributed to the rarity of the extractor.

The early extractors from the 1870s had the technology of the time, cast-iron honey gates. The old-style honey gate somewhat resembled a water spigot. A short horizontal pipe extended from the can, then turned downward with a gentle bend. A flat closure slid over the end of the pipe with a small handle projecting opposite from the hinged side. The extended handle provided leverage to manipulate the gate. While this honey gate design persisted for many years, it had an inherent flaw.

Dropping the extractor from even a modest height (a few feet) could shatter the gate because it was made from strong but brittle cast iron. When broken, I usually see only the bare pipe remaining. What became of extractors with broken honey gates, left always open, is hard to say. They could have been discarded prematurely for scrap metal. Maybe their owners demoted them to just trash cans (basket removed), or just abandoned them to rust away. On the other hand, beekeepers being inventive, our timeless quality, could have found ways to fix the gate or just use the extractor gateless, letting the honey continuously drain into a lower small tank or pail while extracting. When first learning of an old extractor or honey tank, one of my initial questions is always: What is the condition of the honey gate?

Another headwind against honey extractors in the 1870s, which continued in to the early 1900s, was the problem of adulterated honey. Cheap sugars were commonly added to liquid honey, increasing its volume, to sell more of it. Adulterated foods were common during this time. Honey however had a particularly pleasing way to skirt the adulteration curse. The bees themselves sealed honey in the comb while still in the hive, all untouched by the greed of the human race. Customers trusted comb honey, purchased in the wooden section boxes. While producing section comb honey required considerable skill, it also avoided the new technology cost of the honey extractor. Beekeepers would soon learn that extracted honey was not only easier to produce than section comb honey, but the crops of extracted honey were generally larger.

After some 30 years of searching and collecting old honey extractors, I finally found a Novice Root extractor in a design extending back to those formative years in the 1870s. Even more astonishing, the extractor had survived remarkably well for over a century, retaining a near pristine condition (see Figures 2 and 3).

The extractor is a two-frame nonreversible design. The frames are positioned in the basket tangential to the central axis (not radially like spokes in a wheel). After spinning out the honey from the outer side of the combs, the beekeeper had to stop the basket, and lift out and turn the frames (manually). Then the beekeeper extracted the honey from the other side of the combs. “Reversible “meant the pair of frames were set opposite to each other in smaller wire “pockets” that were hinged to swing like gates. After extracting one side of the combs, the beekeeper just stopped the rotation, reached into the extractor, and quickly pivoted the frames, putting the unextracted side outward. In later years, some Root extractors boldly proclaimed on the can that they were Automatic extractors. Automatic meant the frames in their hinged pocket were configured so that a minor application of the brake automatically pivoted the frames without even stopping the rotation. (I have an old Automatic extractor, and it does work.)

The good fortune with the extractor’s assessment continued on to its honey gate, a part often broken as mentioned above. Figure 4 shows a general view of the gate. From the hinged side, the handle extends past the pipe, and provides additional leverage to adjust the honey moving through the pipe. The gate was completely intact, right down to having the old rubber grommet to seal the closure, something hardly ever observed (Figure 5).

Now we come to the height of the can, or here the lack of it. The short can (17.5 inches tall as stated in the older Root catalogs) was offered until sometime in the summer of 1891. (That termination time is approximate because I only have a low density of Root catalogs during that time). Nevertheless, when I see a short extractor, somewhat squarish, I think, nonstandard frames, start test fitting with the square ones (see Figure 6). Initially upon seeing the extractor, I figured it took a Gallop frame (11 ¼ inches square), which turned out to be a fortunate guess (see Figure 7). Gallop was a well-known beekeeper in that time period. Many beekeepers liked his frame size. American frames (12 inches square) were well known too. A couple of frames were close to square. Standard frames (13 ¾ by 11 ¼ in), as beekeepers ironically called them (no frames were standard), seemed popular for a while (and then I think they fell from favor). Adair, a famous beekeeper from Kentucky, had frames 13 3/8 by 11 ¼ inches.

After I acquired the green Root extractor, while dreading the credit card bill soon to arrive, the craziest thing happened. Another ultra-rare extractor popped up for sale. This one was way out west. I marveled my way through the auction pictures, the images playing like a big movie screen in my mind. In near pristine condition, I thought, like the first. This extractor had a similar lettering style, and a color definitely fading from a bold yellow long ago. The main difference with this extractor –– the can was never painted. Unpainted and in green, I thought, were these the precursors of the beautiful blue Root extractors yet to come in later decades? From the digital pictures, I could not tell frame size for the second extractor. Based on my studies of apiculture, I ranked the possibilities starting (very roughly) with the most likely: Gallop, American, and maybe Adair. So, I was figuring the second extractor would take the same nonstandard frame as the first.

Contemplating the high cost of a second extractor and another hefty shipping bill, while knowing it was mostly a duplicate, do you think I wrestled with whether I should buy this second extractor? Of course not. Not after 30 years of hunting these elusive extractors. And besides, I obeyed my long-held collecting maxim: When suddenly confronted by extremely rare bee antiques/artifacts –– Buy All of Them (and try not to go broke, aka, the tricky part). I also know it is an exceptionally bad mistake to think you know “everything” just from seeing one particular extractor design or smoker design, etc., like seeing one old Novice honey extractor or one Clark bee smoker. Artifact histories are often richly detailed with variation, leading to unanticipated new observations. Figure 8 shows the second Root extractor and the current design element I am investigating as a possible way to date this particular extractor (Figure 9).

After I had both Root extractors for a few weeks, guess what happened? Another ultra-rare extractor mysteriously appeared for sale. This extractor had its own honey tank built in below the basket, a design I had been hunting for decades. Oh yes, I bought that one too. We met it in the previous article.

Naturally one may wonder: How can three extremely rare honey extractors come up for sale so close together in time and from distant places around the country? It would be quite unusual if these events were independent of each other, meaning the occurrence of one rare extractor sale had no influence on the occurrence of later extractor sales. These events are not independent.

Sellers, having similar old extractors, seeing the prior auction results that could be near their own sales results, quickly offered their extractors too. This chain reaction of selling such exquisitely rare extractors is not…