The last two months I have been talking about polyandry – the queen’s habit of mating with many males – and the benefits it confers on her colony. Colonies with polyandrous queens are more disease resistant1,2,3 resist Varroa mites better , and reproduce (swarm) more successfully5, the latter of course not being good for a honey producer, but nevertheless is the real currency that counts from a natural history perspective. Last month I presented evidence that a hyperpolyandrous queen – one mated to significantly higher-than-average numbers of males – captures rare resistance alleles that help her colony resist disorders such as Varroa mite. Moreover, artificial insemination may be a way to produce these queens and deliver the benefits of hyperpolyandry to the beekeeping industry.4

I must hasten to say that the potential benefits of polyandry for the beekeeping industry have been recognized and studied by many. David Tarpy, Dennis vanEngelsdorp, and Jeff Pettis sampled 81 colonies from three migratory operations on the East coast and found that average mating number of these queens was 13.6±6.8 males, but that within this range there was no consistent benefit of polyandry on queen supersedure rates. The data were messy and serve as an example of how resistant biological data can be to providing consistent answers. Even though there was no average difference in mating number between queens who superseded and those that did not, among those that were superseded the more males they were mated to the shorter was their lifespan. In spite of this noise, these authors still found that, overall, colonies whose queens were mated with fewer than 7 males were 2.86 times more likely to die before the end of the study than those whose queens were mated to more than 7 males.6 Thus, the bulk of evidence still supports polyandry.

Debbie Delaney and her co-workers did a descriptive analysis of queens from 12 commercial queen producers in the Southeast and West7 for numerous measures of reproductive quality. The average mating number of these queens appeared to be good (16.0±9.5 males), debunking a popular myth that modern commercial queens are “not mated good enough;” however there was a lot of variation among queen producers indicating that mating quality may be inconsistent. Queen mating number was also positively correlated with thorax width, and the authors discussed the possibility “that a larger thorax presumably indicates larger flight muscles, which may enable queens to fly for longer durations on their mating flights and therefore mate with more males,” while at the same time pointing out other authors who had shown no effect of mating flight length on mating number or stored sperm counts.

So it appears that with polyandry as in so many other measures in biology, bee scientists and beekeepers should become comfortable with a degree of ambiguity. Nature is complicated, factors are interacting, and silver bullets are hard to come by whether they are man-made or the products of evolution.

That said, I am still firm in my conviction that polyandry has been neglected and that it represents an important untapped resource for improving queen breeding. I’m reminded of a passage I wrote in this column in February 2014:

The strength of a scientific explanation is greater or lesser depending on the quantity, quality and consistency of the evidence, and the best kind of evidence is one or more independent studies, each challenging the hypothesis and each finding results consistent with the others. Repeatability is a good thing and increases our confidence that the conclusion is robust under numerous conditions.

If the principle of repeatability is reliable, then we can say with confidence that polyandry is good “under numerous conditions.” The evidence for its positive effects on colony strength and disease resistance draws upon numerous papers over time and place.

So a big question taking shape is: How can queen breeders improve polyandry in their queens? Instrumental insemination is one way, but this technology is admittedly expensive, requires investment in specialized training, and has not yet achieved widespread use in spite of its availability in its present state for over 60 years.8 Are there field-friendly methods queen breeders can employ? The short answer is, We don’t know. Or more specifically, I don’t know. It’s a topic for grant proposals, new research, and subsequent reports to the beekeeping industry in forums such as this magazine. But as I’ve said before in these pages, studying the biology is a first good step.

And that brings us to the other side of the equation about polyandry, and that’s the part played by the drones the polyandrous queen mates with. Males of the genus Apis are conspicuous for their so-called drone congregation areas, or DCAs. Beginning around

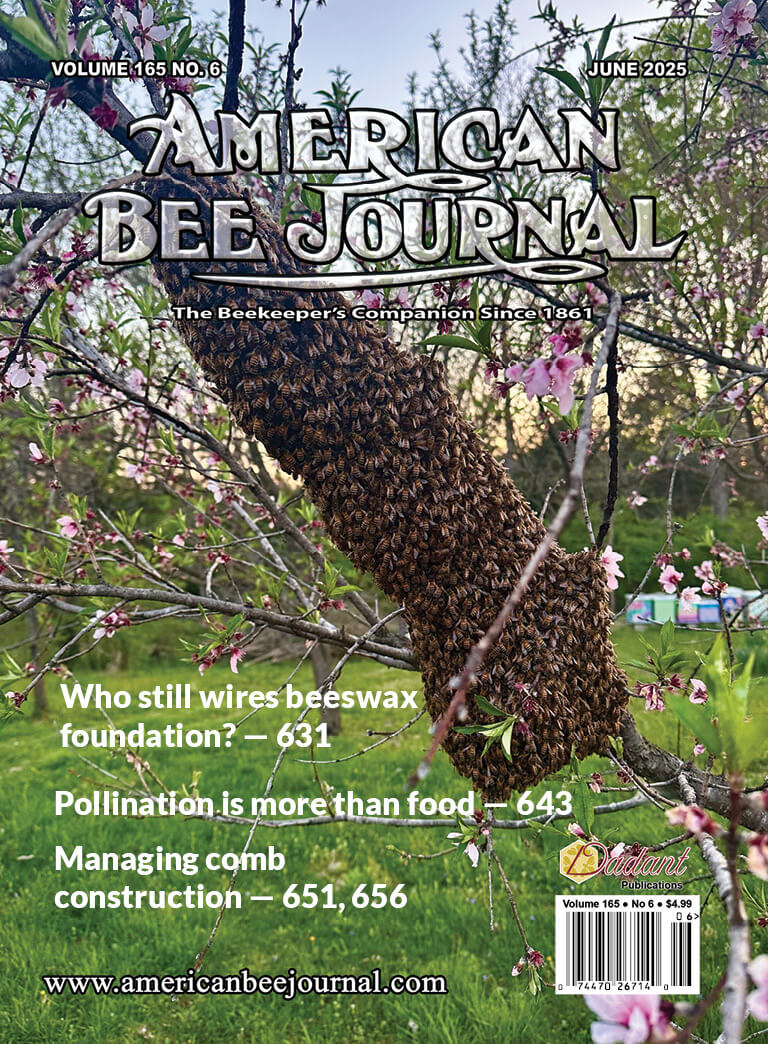

PHOTO CAPTION

Figure 1. In my book, First Lessons in Beekeeping, I talk about Mr. Karl Showler who made a life hobby of tracking DCAs and documenting their permanency over a span of decades. He attracted drones and monitored drone flyways in the borderlands between England and Wales by suspending from the end of a cane fishing pole a chalk lure, painted black, and soaked in alcohol extract of dead queens. Among his many interesting findings was a persistent DCA that oriented around the demarcations of an ancient Roman military road.