Archived Columns

More on corbiculate bees, and arguments for a European Origin for Apis

Since January 2015 I’ve been writing a monthly serial on the social evolution of the honey bee. Both words count: social and evolution. Social in distinction to individual selection that produces basic body plans, and Evolution in the sense of those genetic adaptations made over time in the context of group living. This is why we’ve not spent a lot of time on such things as honey bee anatomy and physiology. Basic anatomy and physiology are ancient features inherited from solitary pre-social ancestors going back 400 million years or more since insects first diverged from their freshwater crustacean forebears.1

By this point in time there are indeed aspects of honey bee anatomy and physiology that bear marks of social evolution. Things like the worker’s barbed stinger that only makes sense in a social context, where a worker would sacrifice herself for the good of the colony. Or the anatomical simplicity of the queen, who has ceded colony maintenance to the worker caste. Or the bouquet of pheromones in the queen’s and workers’ repertoires that only make sense in a social context.Since January 2015 I’ve been writing a monthly serial on the social evolution of the honey bee. Both words count: social and evolution. Social in distinction to individual selection that produces basic body plans, and Evolution in the sense of those genetic adaptations made over time in the context of group living. This is why we’ve not spent a lot of time on such things as honey bee anatomy and physiology. Basic anatomy and physiology are ancient features inherited from solitary pre-social ancestors going back 400 million years or more since insects first diverged from their freshwater crustacean forebears.1ince January 2015 I’ve been writing a monthly serial on the social evolution of the honey bee. Both words count: social and evolution. Social in distinction to individual selection that produces basic body plans, and Evolution in the sense of those genetic adaptations made over time in the context of group living. This is why we’ve not spent a lot of time on such things as honey bee anatomy and physiology. Basic anatomy and physiology are ancient features inherited from solitary pre-social ancestors going back 400 million years or more since insects first diverged from their freshwater crustacean forebears.1

But these changes are derived – later anatomical or physiological modifications made in response to socially-sensitive dynamics the species was responding to in geological time. It is these socially-sensitive dynamics that I find more interesting. The fact is, honey bee evolution has proceeded at two levels – the individual and the group, and it is the group half of that equation that has dominated our discussions in this column.

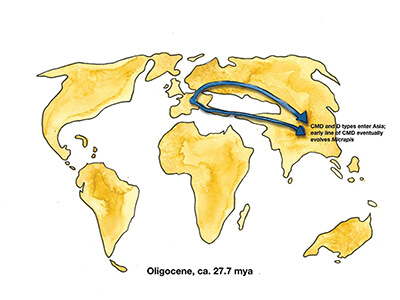

Many of the evolutionary mileposts I’ve talked about over the last 40 months happened before the genus Apis even existed. As last month’s article points out, it was during the evolution of the corbiculate bees, the immediate ancestors of the genus Apis, that the pillars of advanced sociality were evolved – cooperative brood care, reproductive division of labor, and overlapping generations.2 So in the spring and summer of 2015 when I was writing about the evolution of worker altruism and the selective powers of kin selection, it was the corbiculate ancestors of the genus Apis of whom I was speaking. No matter. Even though these dramas played out in a string of long extinct corbiculate species, thanks to the Darwinian principle of descent with modification, these are the social features inherited and expressed by the modern honey bees of today.

A few other features of the corbiculate bees are worth mentioning. It is because these bees have representatives spanning all grades of sociality – from solitary to highly social – that investigators have long looked to the corbiculate bees as a testing ground for the evolution of sociality.

So an obvious question is what, if any, relationship is there between sociality and the possession of a corbiculum – the pollen-carrying apparatus situated on the outer side of the hind legs? A corbiculum is not necessary to bee eusociality, as proven by the existence of three eusocial tribes – the Allodapini, Augochlorini, and Halictini – who lack it, but possession of a corbiculum is certainly friendly to eusociality. Not only was the evolution of eusociality much earlier in the corbiculate tribes3, it is the corbiculate bees who today possess the most socially complex bee species.

It was the opinion of Charles Michener that “it is probably easier to remove pollen from a corbicula than to remove an equal amount of pollen carried within a brush of hairs.4” If so, then one can imagine a certain economy of scale and efficiency in pollen handling that would be a preadaptation favorable to social life.

There are a few structures technically corresponding to corbicula in other bee groups; however only in the “true” corbiculate bees is the pollen first moistened with nectar to help hold it in place during transit. The pollen is carried dry in the other corbiculate groups.4 This habit of dampening pollen with nectar strikes me as another preadaptation favorable to social life. It has long been known that bees ferment pollen to acidify it and prolong its storage life in the nest5, and it has recently been shown that the bacteria responsible for this fermentation indeed reside in the honey stomach from which the forager regurgitates nectar.6 Long-term pollen storage is important for a colonial species that lives together as a group year-round.

And a final feature of the corbiculate bees seems important, not so much for the evolution of eusociality, but rather the style of eusociality to which we have become accustomed in the honey bees – and that’s …