Archived Columns

Life Without Fumagilin

The only registered treatment for Nosema disease is no longer commercially available.

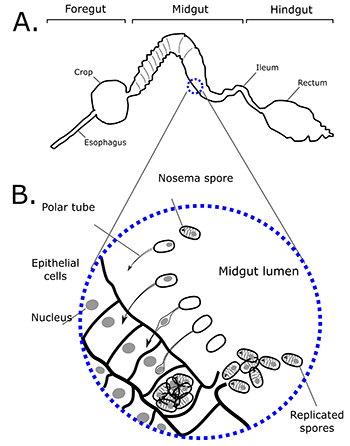

The harpoon shoots out from its egg-shaped case like a microscopic military-grade weapon. It hits its target – a honey bee midgut cell – dead on, piercing the cell membrane and latching on. But the harpoon was not built to kill (at least not right away). Instead, still attached to its case via a tubular tether, it begins injecting infectious material into the host cell, seizing the cell’s resources to do its bidding in as little as two seconds. The poor cell has no choice but to comply, facilitating the mass production of more tiny, egg-shaped spores until it ruptures, releasing new spores into the gut to begin the cycle anew. More spores find more cells to infect, and the nosema infection spreads.

Nosema spores might look nondescript, but their modus operandi is anything but. The microscopic spore particles drift in the honey bee’s midgut lumen, waiting to come across the unsuspecting epithelial cells lining the gut wall, and then they strike (Figure 1). Nosema disease, or nosemosis, is now the most globally prevalent honey bee disease, and in some regions (mainly in the Mediterranean), it can be devastating.1 Although once thought to only affect adult bees, it can actually proliferate in larvae too.2 The only approved treatment against nosemosis is the antibiotic fumagillin, but now, it’s no longer for sale.

On April 12, 2018, Medivet Pharmaceuticals Ltd. – a company based out of High River, Alberta – announced that they were closing their doors. And shutting down Medivet means shutting down production of the world’s supply of fumagillin, in the form of their quick-dissolving product, Fumagilin-B. “The production and sale of Fumagilin-B has been the bread and butter of Medivet Pharmaceuticals for many years,” Ursula Da Rugna, president of Medivet, wrote in a public letter announcing their closure. “Once all our inventories have been sold we will dismantle our facilities; it is expected we will be closed by June 2018.”

Medivet’s ghostly website still warns of a scam, where an unknown, ineffective substance was being sold cheaply under the label of Fumagilin-B. But this fraud, which was confined mainly to Middle-Eastern countries, is not what forced them to close.

Medivet relied on another company, CEVA Sante Animale in Libourne, France, to supply the active ingredient in Fumagilin-B: fumagilline DCH (which stands for dicyclohexylamine). But for reasons that aren’t clear, CEVA Sante Animale’s outsourced manufacturer is no longer allowed to produce it, and it’s unlikely that another company will step in soon to fill their shoes. “I don’t know of another company that can do it,” Ursula says. “Without fumagilline DCH, no more Fumagilin-B can be produced.”

Now, as we tip-toe into fall – when most beekeepers would begin treating for nosema – many are wondering where to turn. After their announcement last spring, Medivet’s Fumagillin-B inventory quickly sold out to their distributors and customers. No doubt some beekeepers have a stockpile of the antibiotic at home, but even that won’t last forever. “There are no other chemical medications approved for treatment of nosema anywhere in the world,” Ursula says. “There are some labs around that are trying to test other compounds to treat nosema, but I don’t know of any that are close to registration and approval for sale.”

This sounds like a disaster, but could it actually be good for the industry in the long term? If there is no longer an effective treatment for the disease, there will be stronger selective pressure for innately resistant colonies over time (although this may not be a practical solution). Understandably, most beekeepers in heavily affected regions probably wouldn’t be willing to risk the losses to natural selection. But fumagillin treatment may not be as beneficial as we think, at least, with the way it is currently administered in practice. Some evidence suggests it may actually be exacerbating infections, rather than annihilating them.

Nosema disease can be caused by two different ….