Long before I knew it had a name, I wrote about the Dunning-Kruger effect in beekeeping. In a blog post titled “I Was So Much Smarter Then,” I revealed the results of my one-sided, unscientific, and misguided study on the knowledge base of beekeepers as it correlates with the time they’ve been keeping bees.

From my extensive research, I discovered that first-year beekeepers know the least. Not a surprise. Many don’t know a mite from a mouse — after all, they both live in beehives — but that’s okay because the beginners absorb knowledge and learn fast. They read, attend classes, ask questions. They are grateful for any help you may offer.

The trouble starts in year two

The practitioners who know the most, those who know everything there is to know about bees, are in their second and third years. If you have a question, they have the answer. If you have an opinion, they let you know what they think of it — and of you. They don’t read, because they could write it better. They don’t listen, because they could say it better.

Trust me, they are beekeeping prodigies. If you need a fast answer and a confident opinion, they are the people to see. If you want an explanation not tempered with caveats, they are the ones to provide it. I am happy for them as they revel in their sea of knowledge.

It’s all downhill after that

Then, long about the fourth year, something happens — their knowledge erodes. It’s not that they know less, but they suddenly grasp the complexity of beekeeping. They realize they’ve learned but the tip of the iceberg.

These more experienced beekeepers see issues as complex rather than simple. They see answers as multi-faceted, not smooth and round. The amount they want to learn gradually becomes infinite. As their knowledge increases, their answers become longer, beginning with phrases like “It depends” or “It could be several things” or “I need more details.”

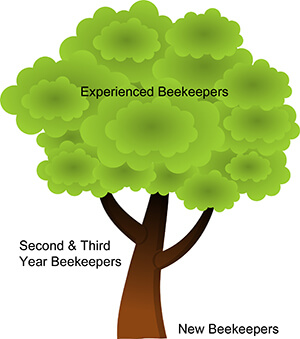

The tree of knowledge

Back in my 2013 blog post, I compared the learning pathway to the tree of knowledge. The first-year beekeepers occupy the ground, right where the tree breaks through the soil. The second- and third-year beekeepers live on the trunk where everything is smooth, well-defined, and orderly. Those who’ve been at it longer are in the limbs, branches, and twigs where every question has a complex answer, and all the pathways are obscured by leaves.

Knowledgeable beekeepers go to lectures, read scientific papers, and experiment. As their knowledge increases in multiples, they feel they know less, yet they want to know more. They are awed by the bees, mesmerized, humbled. They never have fast answers, only well-considered opinions tempered with experience and the realization that, with bees, there are no simple answers.

Beekeepers are not alone

While I was busy thinking my observations were brilliant, I did not know of the research reported by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger at Cornell University. In 1999, they published a paper titled, “Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments.”1

In part, the paper says that incompetent individuals dramatically overestimate their own ability and are unlikely to recognize competence in others. It’s not until they eventually become more competent that they realize they were ever incompetent. Conversely, those who are truly competent often underestimate their ability as they embrace the intricacy of their subject.

According to an article in Psychology Today, the tendency to overestimate one’s own ability “may occur because gaining a small amount of knowledge in an area about which one was previously ignorant can make people feel as though they’re suddenly experts. Only after continuing to explore a topic do they realize its extent and how much they still have to master.”2

The crash before the climb

The best thing Dunning and Kruger gave us is their curve. The curve shows that as a beginner we start from zero and learn fast. Our self-confidence ascends like a rocket, nearly straight up. When we’re on the top of the curve — which doesn’t take long — we know it all.

Unfortunately, while we’re sitting at the top, we don’t know what we don’t know. Characteristically, our confidence doesn’t stall until something causes us to question our own ability, something like an apiary full of dead-outs. Then we avalanche to the bottom of the chart, landing in a humble heap in a deep trough.

But after that, true learning begins. In a painfully slow process, fallen messiahs brush away the humiliation, shed the arrogance, and begin a journey toward enlightened beekeeping. The second hump on the Dunning-Kruger curve is where we all want to be. This is the place where true experts reside and thrive.

I used to know it all

I am speaking partially from experience gathered from my website, classes I’ve taught, and lectures I’ve given. Sad to say, I’ve also been there myself. I used to know much more about bees than I do now. In fact, I used to know just about everything.

However, once I began studying bee nutrition, pathogens, pesticide interactions, reproduction, genetics, health, hygienic behavior, flower selection, pollen composition, bee communication, social interactions, nest-site selection, and environmental stressors, something happened. I knew less and less every day until I knew — and still know — almost nothing. I soon realized I had but one short lifetime to puzzle through an endless assortment of parameters, confounding variables, inconvenient facts, and scads of combinations and permutations.

Too much help from the top

The most troublesome beekeepers are the ones who rapidly ascend the steep slope and get stuck at the peak, sometimes for many months or even years. Having learned everything there is to know in ten months, they contemplate us mere mortals from their aeries in the sky and condescend to help.

And what do they do? They share their ineptitude. They pontificate in books and blog posts and ….