Using bees to deliver targeted biological control agents to flowers could be the next big thing for precision agriculture

Humans have been designing pollination robots since at least the 1990s, but try as we might, so far nature has produced the best pollinators we have. Bees have delicate dexterity, wonderfully small, fuzzy bodies that tickle the anthers just right, and an unsurpassed aptitude for flying from flower to flower. But pollen is not the only beneficial cargo that bees could spread among flowers.

In an approach called “bee vectoring technology,” or, more generally, “entomovectoring,” scientists are developing new methods of using honey bees, bumble bees, and orchard bees to deliver biological control agents to crops. The idea is that, since many plant pathogens spread by inoculating flowers, farmers could prevent disease outbreaks by getting bees to deliver beneficial microbes to the flowers first, which either outcompete or outright kill the would-be infectious agent.

Fighting the blight

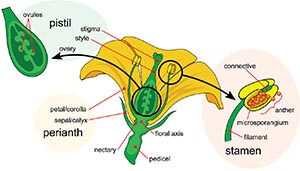

Apple and pear trees, for example, are susceptible to a disease called fire blight, which is caused by a bacterial infection that first colonizes the stamen (the flower structure that includes the anthers). The infection can later spread to the rootstock and eventually kill the tree. In 2000, a fire blight epidemic in Michigan killed up to 400,000 trees and caused tens of millions of dollars in losses.

This disease and others are the reason why farmers apply upwards of 17,000 pounds of streptomycin antibiotic to apple and pear trees each year in the U.S. As expected, resistant forms of Erwinia amylovora (the causative agent of fire blight) have emerged, and while oxytetracycline is also a registered treatment for the disease, resistance to that is emerging as well.

However, several types of non-pathogenic bacteria can prevent fire blight, provided they colonize the stamen first. Some of these bacteria are already formulated into registered blight-prevention products, such as Serenade, but are not often used in part because of difficulty inoculating the delicate stamens. Who better to do this job than a bee?

Dr. Neelendra Joshi, an associate professor at the University of Arkansas who specializes in pest management and pollinator health programs, and Dr. David Biddinger, a tree fruit research entomologist and professor at the Pennsylvania State University, are studying how the Japanese orchard bee (Osmia cornifrons) can be used to apply Serenade to apple flowers.1 Serenade is a biological control product containing the bacterium Bacillus subtilis, which can colonize the stamens of flowers and effectively prevent fire blight infections by outcompeting new invaders.

Awe for Osmia

“Osmia corniforns and other Osmia species are very efficient pollinators of spring flowering rosaceous fruit crops like apples and cherries,” Joshi explains. “They are covered with a lot of body hairs that provide efficient ways to collect vector particles while exiting the dispenser nest-box.” Since orchard bees also have life cycles that are well-timed for early-season crops, are more loyal to fruit trees than honey bees, and are more efficient pollinators on a per-visit basis, they are good candidates for delivering Serenade to flowers. However, as solitary bees that are sold as “bee condos” of nesting tubes, devising a strategy to load the orchard bees with their new cargo was a challenge.

Biddinger and Joshi developed a specialized bee condo with grooved exit ramps: When Serenade is loaded into the grooves, the orchard bees get dusted with the product as they leave the condo. In a collaboration with Dr. Henry Ngugi, a plant pathologist, Biddinger and Joshi found that, on average, each bee exiting their device carried about 9-13 million bacteria, which translated to the surrounding apple flowers getting 50,000-90,000 bacteria each.

The researchers conducted this work in a greenhouse to ensure that their bees were the only ones that could be vectoring Serenade to the flowers. But they also wanted to test if clean bees could spread the product from previously inoculated flowers to naïve flowers. To do this, they moved the small apple trees that were already exposed to Serenade out of the greenhouse and next to unexposed trees, along with a bee condo that contained no Serenade.

Encouragingly, they found that just one day after the move, B. subtilis colonized the unexposed flowers, too. Since the previously inoculated flowers were the most conspicuous source of B. subtilis around, the naïve flowers probably gained their own bacterial colonies from the otherwise clean bees transferring bacteria between flowers. Moreover, the B. subtilis population grew as time went on, creating what the authors call a “self-perpetuating system.”

“All pollinators visiting the inoculated flowers, not just O. cornifrons [the Japanese orchard bee], should be able to move the B. subtilis colonies to new flowers as they open,” the authors write, while emphasizing that more work needs to be done to determine optimal stocking densities and how often the inoculation ramps need to be refilled. “We are working on optimizing dispenser systems and looking for different ways to refine biopesticide formulations to use with different species,” Joshi says.

Helpful honey bees

Other researchers have investigated using honey bees as vectors of Serenade to blueberry flowers, where the B. subtilis colonization can help prevent berry mummification by the fungal pathogen Monilinia vaccinii-corymbosi. However, the bees are also excellent vectors for the ….