What should you do when something comes between you and your honey bees? Perhaps something like a walker or wheelchair? Well, if you are creative and innovative, you might discover the perfect solution — one that works for you and pleases your bees.

Master beekeeper Naomi Price of Prineville, Oregon did exactly that. Living with paraplegia, Naomi knew she wanted a hive that would meet the needs of her bees as well as a few of her own. Simply put, she wanted the freedom to tend her bees without assistance from others. “Accessibility is all about attitude,” she said.

Starting with a Vision

Armed with spunky determination, Naomi set out to make her beekeeping dream a reality. Having spent years performing accessibility site surveys for various entities under the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Oregon Structural Specialty Code, she was the perfect person for the job. She understood that small things make a big difference. “Just as a 3/8-inch space can be empowering to a honey bee, a 1/4-inch space can be equally empowering to me,” she explained.

To start, Naomi put aside the codes and regulations and began to investigate the honey bees’ housing requirements. She studied foraging, brood rearing, food storage, communication, ventilation, winter clustering, pests, and even her local weather patterns. After that, she looked at the history of hive design, taking careful note of what worked and what didn’t. Finally, she factored in her own beekeeping experience, including the special features she needed for successful and enjoyable beekeeping.

Finding a Builder

Richard Nichols, a Prineville resident, built the prototype long hives. A skilled woodworker with a passion for beekeeping, Richard was able to incorporate Naomi’s vision within the practical limitations of building with wood. The finished product exceeded all expectations and many of the original hives are still in use.

Valhalla Features

The first rendition of her hive design — christened the Valhalla — was a variation on the Langstroth long hive made popular by Georges de Layens in his book, Keeping Bees in Horizontal Hives. Basically, a long hive is a horizontal hive that uses standard Langstroth frames. Instead of using supers that stack on top of the brood box, the bee colony expands horizontally, much like the bees in a top-bar hive.

But the similarity stopped there because Naomi needed to incorporate special features which would allow for the ease of access she needed. She wanted a system that didn’t require extra tools and equipment, and one that would be winter-ready without lifting, carting, and storing hive components.

Many design considerations were incorporated into the prototype hives, including the following:

Frames. The Valhalla hive uses 24 deep Langstroth frames. Naomi selected the number of frames based on the nectar flow near her central Oregon home and the colony’s winter clustering needs. Some of the frames provide space for honey storage that would normally go in a super.

By using Langstroth frames, Naomi could easily exchange equipment between her long hives and Langstroth hives. In addition, four-sided frames can be rested on the ground or other hard surface without damaging combs, a feature missing in top-bar hives. But most importantly, a standard nucleus colony can be inserted directly into a Valhalla hive — another feature that was impossible with most top-bar systems.

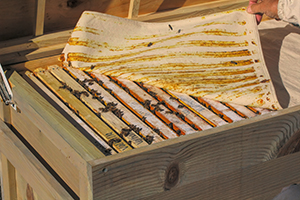

Canvas Frame Cover. A heavy canvas cloth placed directly on the top bars keeps the bees from building burr comb above the frames. When Naomi is working the bees, the canvas can be gently folded back from one side or the other, keeping the rest of the bees calm and in the dark. The workers propolize the cloth, thereby adding an antibacterial barrier just above the brood nest.

Hive Box. Having a low profile, the long hive is stable in the face of wind and predators such as raccoons, so it doesn’t require the inconvenience of a tie-down. And since there are no supers to lift, hive inspections are a snap.

Hinged Roof. The roof is hinged on the front side so the beekeeper can easily work the bees from the back. A side latch holds the roof open, even in moderate wind. In the open position, the lid protects the brood nest from both sun and wind.

Slatted Rack. A built-in slatted rack extends the entire length of the hive, offering foragers a place to cluster when summer temperatures rise. Below the slatted rack are two side-by-side pull-out inspection drawers that can be used for varroa counts and debris collection.

Entrance. A single bee entrance is in the lower right corner of the hive. It measure 3/8-inches high by 3 inches long and has a sliding door to adjust the size of the opening or close it completely. The small size and adjustable nature mean it can double as a mouse guard during those times when rodents are likely to enter.

The entrance has no landing board. Naomi notes that, without a landing area, honey bees experience fewer run-ins with nest mates and fewer intruders. In addition, the entrance is easier to defend since there is no convenient staging area for evil-doers. “I have observed the returning foragers fly into their hive with amazing accuracy,” she says.

Viewing Window. The hive is equipped with a Plexiglas viewing window with a hinged shutter that allows a quick peek into the brood chamber without opening the lid.

Inspections are Easy

Inspections are far more efficient when you don’t have to remove supers before getting to the brood box. In addition, inspections in the Valhalla are far less upsetting to the colony. Naomi says, “With no boxes to move, fewer bees are injured, which means the bees are less defensive.”

By folding back only part of the canvas cloth at a time, the bees are ….