Finding an antique bee smoker, maybe over a century old, can be thrilling. You could be holding the hopes and dreams, the thrills and disappointments, of a beekeeper, usually more than one, from moments long forgotten. Accurately identifying and dating a smoker, backed up by literature with matching pictures, can turn frustrating and problematic. Some old smokers cling tightly to their secret origins.

The old apiculture literature can identify vintage smokers, mostly manufactured ones, not the handmade creations. Looking through old bee journals, some issues might show the unidentified smoker in advertising pictures. The problem with identifying smokers from bee journals is that in the old format the text, articles, etc., were all compiled together. The advertisement pages wrapped around the text pages. The front and back covers and the advertisements formed the beginning few pages and the last few pages. These advertising pages are called the wraps because they wrapped around the text. When binding journals into a book form, the wraps were usually removed to slim the volumes and save shelf space. While month-to-month, advertisements can be quite redundant, that repetition is an indication of the production life of apicultural equipment, quite important for historical studies. Moreover, removing all the wrappings strips away a considerable amount of history, not to mention the artwork of the front covers. Even digital copies suffer from wrap removal if they were copied from bound copies of journals whose wraps were removed long ago.

With a reputation for being difficult to find, old bee supply catalogs can identify numerous smokers and provide original designs and production years. In the past, numerous small factories made a great diversity of smokers. It is typical to have several smokers in a collection, known to be factory made, whose origins came from some small factories with a very limited supply catalog publication of maybe only a few years. (Other production possibilities are local tinsmiths and blacksmiths with no literature documentation.)

Against these headwinds obscuring the origins of old bee smokers, I want to concentrate on a design that does not receive much attention. Their funnels point to the side, but with a crook or joint in them, not a straight side slant funnel, as on the modern smoker. While a smoker’s funnel draws considerable attention for identification, I have found over the years that the design of the attachments connecting the bellows to the fire barrel (the metal barrel) can be critical in bee smoker identification as we will see in the following examples.

The Leahy Manufacturing Company was located in Higginsville in western Missouri, near Kansas City. Figure 1 shows a Leahy bee supply catalog. In 1908, the Company boasted the connection to 20 railroad lines. (Long before cars, trucks, and interstate highways, America was a railroad culture. Bee suppliers often lauded their railroad connections, supporting claims of fast and efficient shipping of beehives, extractors, etc.)

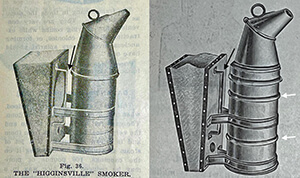

Their catalog, dated to about 1908 (the year found in a testimonial letter), shows the Higginsville smoker (see Figure 2, left). For beekeepers of the times, a funnel projected to the side, providing an easier application of smoke compared to the older funnels pointing straight up. To smoke bees with a funnel pointing straight up, the beekeeper had to point the smoker downward. Occasionally hot ashes fell on the bees, which no doubt wreaked havoc on them. In the old beekeeper slang, this notorious problem even warranted its own descriptive name –– fire dropping.

Figure 2 (right) shows the Higginsville smoker from the 1923 Leahy Catalog. In this version, the lower straps bend inward, possibly to increase the stability of the connection between the bellows and fire barrel. In the rolled metal forming the barrel of the smoker two rings appear. These grooves, rolled into the metal, project out and appear as rings functioning as stiffeners to form a stronger barrel.

Finding Higginsville smokers of this time period is difficult. They may have various small modifications differing from known catalog pictures, although the overall design should match quite well (see Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 5 shows a Higginsville smoker that I have not seen in the literature so far. The design may have been an attempt to solve a possible chronic problem. In the versions discussed above, the straps hold the hot metal fire barrel away from the front wooden bellows board. With considerable use, the connection might have become weak, perhaps loose. The Higginsville smoker in Figure 5 has a wooden spacer, attached to the front bellows board. Sheet metal covers the wooden spacer to protect it from burning. Straight metal straps pull the fire barrel against this spacer, giving another point of contact for more stability. Figure 6 shows a closer side view of the spacer.

Kretchmer Manufacturing Company was a firm once located in Council Bluffs, Iowa. Old Kretchmer bee supply catalogs and smokers are difficult to find. Figure 7 shows an early smoker in mint condition, given its age. I estimate its age to be before 1915, probably much older. I do not have catalog documentation on this smoker. However, if a smoker had a light service life and a favorable storage environment, its own documentation may have survived. Some manufacturers put a paper label on the valve that lets air into the bellows when it expands. Figure 8 shows the label for the smoker in Figure 7. Without a definitive label, the connection between the fire barrel and bellows is another important place to study to identify a smoker (see Figure 9).

The new part here is the distinctive pipe connection at the bottom of the bellows, where a modern smoker has only a gap where forced air leaves the bellows and enters the fire barrel. Curiously, the pipe connection has a large opening to let in air while the smoker is not in use. (Leaving a gap was patented by T.F. Bingham in 1878, and is called the direct draft principle. The gap allows a little air flow through the fire when the smoker is not in use. This air flow, or direct draft, keeps the smoke going, not leaving beekeepers exposed to irritated bees. Bingham was known to protect his patent.)

By 1915, Kretchmer catalog pictures show a redesigned smoker….