Is Darwinian beekeeping compatible with industry?

“Honey bees are the best beekeepers,” Dr. Tom Seeley softly declared to a captivated audience. The room was packed, shoulder-to-shoulder, and everyone was attentive. It was the final day of the Apimondia conference in Montreal, Canada, and Seeley held the last keynote address. “Everything they do has been shaped by natural selection. Maybe we should let the bees be the beekeepers.”

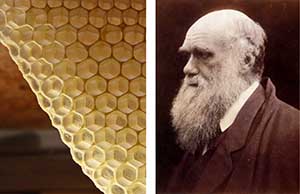

Seeley — an esteemed author and professor at Cornell — used the stage to educate us all about what he calls Darwinian beekeeping, and it’s probably not what you think. Darwinian beekeeping is not exactly natural selection, nor is it forsaking basic animal husbandry and leaving the colonies to fend for themselves. Darwinian beekeeping is about carefully and deliberately modifying our management strategies to return our colonies to as close to a natural state as we reasonably can. It’s about coaxing the fittest colonies to propagate, not based on the test results for a single beneficial trait, but based on the colony’s ability to persist through the myriad of challenges in our ever-changing world. It’s about giving colonies every chance to succeed on their own, through the mites, the seasons, the pathogens, and the contaminated forage, with minimal intervention by us. It’s about cutting our losses. It’s about thinking like a honey bee. And it’s not for commercial operations.

“The colonies are still managed, but in a different way,” Seeley explains. The more we learn about how honey bees manage themselves, the better of a chance we can give them to survive. But few of the Darwinian beekeeping principles can be integrated into a commercial management plan. More typically, adopting the Darwinian method works only for the modest, educated, motivated beekeeper. The kind of beekeeper who is not concerned with expanding their operation. The kind of beekeeper who is in it for the pleasure rather than the profit. And the kind of beekeeper who is fine with their colonies producing less honey if it means they will be healthier.

And they will be healthier, with higher survivorship — eventually. The first principle of Darwinian beekeeping is to encourage propagation of survivor colonies — that is, the colonies that survive year after year without medication — by rearing new queens from them and allowing them to have ample drone comb. But by definition, creating the conditions that let us identify survivor colonies means that many of the other colonies will die. It’s a tough pill for an empathetic beekeeper, and not a loss that any commercial beekeeper would be willing to take.

Dr. Peter Rosenkranz, a professor at the University of Hohenheim, Germany, illustrated what this selection process looks like with a vivid anecdote. Rosenkranz also delivered a keynote address at Apimondia on “Worldwide perspectives on bee health.” In it, he described how the Swedish Gotland bees — an isolated population of survivor colonies — came to be. It was a fraught, emotional journey.

The research team brought a population of 150 colonies to an isolated island in the Baltic Sea (Gotland Isl.), gave them an initial dose of mites, then waited six years to watch the mite-survivors emerge (all the while, recording health metrics like swarming frequencies, population size, mite levels, and winter survival).1 During the keynote, Rosenkranz showed us a picture of one of the managing beekeepers — an ex-police officer — sitting dejected in the apiary. “In that moment, he was in tears,” Rosenkranz said. Eighty percent of the colonies the man was overseeing had died that year. Rosenkranz went on to describe how the colonies that remained, while boasting high overwintering survival rates and low mite levels, were nasty and unproductive. Natural selection can bring even the toughest beekeeper to tears.

Rosenkranz and his research team were not exactly practicing Darwinian beekeeping, but their natural selection study illustrated some of the challenges that a Darwinian beekeeper could encounter. The ninth principle of Darwinian beekeeping that Seeley presented is to refrain from treating for mites, and to eliminate colonies with high mite loads. The Gotland experiment stayed true to that principle, and what they ended up with were indeed mite-resistant survivors. They just weren’t the kind of bees that anyone would want to keep.

Seeley notes that in his own experience with colonies in the Arnot Forest, survivors have not been unusually defensive. This suggests that there is, perhaps unsurprisingly, an element of luck involved in letting nature take its course. If your livelihood depends on your bees, luck is probably not a factor you would like to entertain. And we should be cautious when extrapolating findings from one population to another, whether it’s unproductive Gotlands or the gentler Arnots.

But there is probably still a lot that a commercial beekeeper can learn from Seeley’s Darwinian principles. Some of them, thankfully, are amenable to an industrial scale. For example, the average ….